Why in News: The term “Necropolitics” is gaining attention due to The Gaza conflict post-October 7, 2023, where mass civilian casualties, including children, are dismissed as “collateral damage”.

Context:

- Renewed academic and media discourse around whose deaths matter and how states decide which lives are grievable.

- Ongoing structural violence in conflict zones, refugee camps, and marginalised communities globally.

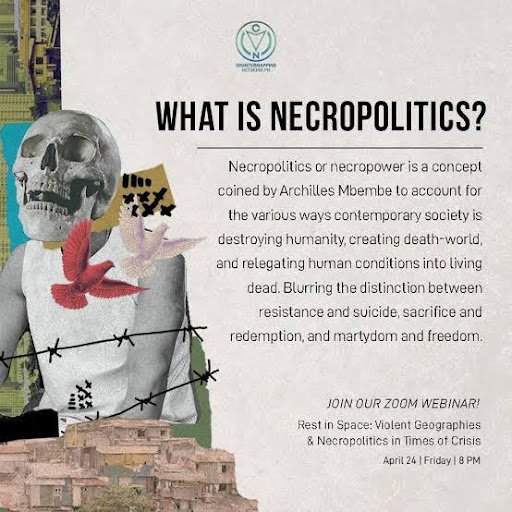

1. What is Necropolitics?

Coined by Achille Mbembe (2003), expanded in his book Necropolitics (2019).

Describes how states and institutions use political power to:

- Decide who may live and who must die.

- Expose certain populations (refugees, racialised groups, the poor) to violence, neglect, or structural abandonment.

Builds on Michel Foucault’s concept of Biopolitics but shifts focus from managing life to managing death.

Comparison of Biopolitics vs Necropolitics

Focus:

– Biopolitics focuses on governing and optimizing life.

– Necropolitics focuses on governing through death or the threat of death.

Methods Used:

– Biopolitics uses vaccination, sanitation, census, surveillance to manage life.

– Necropolitics uses war, starvation, detention, abandonment to control or eliminate.

Key Concern:

– Biopolitics is about “making live and letting die” – promoting life, with passive death.

– Necropolitics is about “letting die and making die” – death is central and often deliberate.

Theorist & Origin:

– Biopolitics was developed by Michel Foucault as a theory of modern governmentality.

– Necropolitics was theorized by Achille Mbembe, building on colonial and postcolonial violence.

Nature of Power:

– Biopolitics exercises productive and regulatory power over life.

– Necropolitics exercises sovereign power through the control of death.

Role of the State:

– In Biopolitics, the state acts as a protector and regulator of life.

– In Necropolitics, the state becomes a decider of who lives and who must die.

Mechanisms of Necropolitics

1. State Violence and Terror

- Use of surveillance, imprisonment, torture, and force—even in democracies—to silence dissent.

2. Collaboration with Non-State Actors

- States often work with militias or private contractors, blurring the line between state and criminal violence.

3. Manufacturing Enemies

- Enmity becomes a tool of governance.

- Entire groups are labeled as threats, justifying state-sanctioned violence.

4. Death as an Economy

- War and terrorism fuel global arms trade and surveillance industries.

- Conflict zones become profitable.

5. Social Displacement

- Resource extraction, urban development displaces vulnerable communities.

6. Structural Death

- Through starvation, disease, slow abandonment (e.g. during pandemics or famines).

7. Moral Justifications

- Nationalism, religion, or utilitarian arguments are used to legitimize policies that lead to death.

State of Exception

Giorgio Agamben: Modern states operate under a “state of exception” where law is suspended to preserve power.

For many, this exception becomes permanent — they live outside legal protection.

Examples:

- Emergency laws used to target minorities.

- Refugee camps, detention centers as zones outside justice.

Living Dead & Death Worlds

Living Dead: People who are biologically alive but stripped of dignity, rights, and recognition.

Examples of Necropolitics

Historical

Bengal Famine (1943): Millions died not due to food scarcity but because of British colonial policies.

Contemporary

- Migrant workers during India’s COVID-19 lockdown: Died from neglect, not virus.

- Gaza (post-October 7, 2023): Bombings of hospitals and homes; children’s deaths dismissed as “collateral damage”.

- HIV/AIDS Crisis (1980s–90s): Queer, trans, and racialised individuals abandoned by health systems.

- Sterilisation of Dalit/Adivasi Women: Covert population control mechanisms targeting marginalised women.

- Drone Strikes: Civilians designated as “targets” without due process.

- Detention Centres: Stateless people and children living in degrading, inhumane conditions

These are Death Worlds — places where death is not accidental but an intended outcome of policy and indifference.

Everyday Necropolitics

- Not just bombs or war, but bureaucratic violence:

- Discriminatory databases and profiling.

- Administrative silence toward mass death or displacement.

- Global indifference to suffering of poor, racialised, or stateless populations.

Resistance and Hope

- The goal must not merely be survival, but to ensure lives are valued, grieved, and protected.

- Resistance means demanding visibility, dignity, and rights for all — especially those systemically erased.

Conclusion

Necropolitics reveals a brutal truth: power today often functions not by protecting life, but by managing death. The challenge lies in recognizing and resisting systems that normalize suffering and make certain lives expendable.

UPSC Relevance:

GS Paper 1 (Society):

Social stratification and marginalization

Structural violence and social injustice

GS Paper 2 (Polity & Governance):

State responsibility in welfare and protection

Human rights and constitutional safeguards

Mains Practice Question

Q. “The power to let die is as politically significant as the power to make live.” Critically examine the role of the modern state in the context of necropolitics.