Why in News: The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is facing a credibility crisis after the controversial transfer of archaeologist K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, linked to the Keeladi excavations in Tamil Nadu.

Introduction

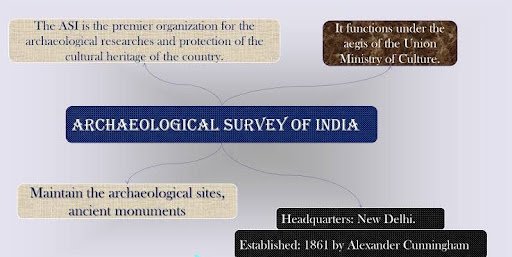

- The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), established in 1861, is entrusted with the preservation, conservation, and research of India’s archaeological heritage.

- However, in recent years, the institution has come under sharp criticism for its handling of key excavation projects, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and politicisation of research.

- The Keeladi excavations in Tamil Nadu and subsequent controversies have become a flashpoint, raising questions about the ASI’s credibility, scientific neutrality, and institutional autonomy.

The Keeladi Case: A Trigger for Scrutiny

Significant Findings: Excavations at Keeladi (2014 onwards) unearthed around 7,500 artefacts, indicating a sophisticated urban, literate, and secular society between the Iron Age (12th–6th century BCE) and Early Historic Period (6th–4th century BCE). Scholars termed it part of the Vaigai Valley Civilisation.

Patterns of Inconsistency in ASI’s Approach

1. Adichanallur and Sivagalai (Tamil Nadu):

- Excavations revealed Iron Age artefacts over 3,000 years old, but ASI delayed publishing findings for more than 15 years until courts intervened.

2. Bahaj Excavation (Rajasthan):

- Discovery of a 23 m-deep paleochannel linked to the mythical Saraswati river and Mahabharata period.

- Shows uncritical acceptance of mytho-historical narratives, compromising scientific objectivity.

3. Ayodhya Excavations (2003):

- Criticised by scholars (Verma & Menon) for lack of scientific integrity and transparency.

Structural and Methodological Issues

Methodological Nationalism:

- ASI often frames findings to fit a state-sanctioned vision of India’s past, privileging monolithic civilisational narratives.

Operational Deficiencies:

- Arbitrary transfers, delayed promotions, inadequate funding, and poor working conditions (Avikunthak, 2021).

Outdated Methods:

- Continued reliance on Wheeler method and absence of comprehensive research designs (Neuß, 2012; Chakrabarti, 1988, 2003).

Closed Review System:

- Most reports remain unpublished or circulated only internally, limiting peer review and global scholarly engagement.

Contrast with Global Practices:

- Institutions such as the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (Germany), INRAP (France), and Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs regularly publish excavation results in peer-reviewed journals, ensuring transparency, accountability, and global credibility.

Implications of the Crisis

- Erosion of Scholarly Credibility: Politicisation undermines ASI’s legitimacy in academic circles.

- Loss of Public Trust: Perception that findings are selectively downplayed or exaggerated for political ends.

- Stifled Research Environment: Bureaucratic hurdles and lack of autonomy discourage genuine scholarship.

- Global Isolation: Limited participation in international academic debates due to non-publication and lack of collaboration.

- Threat to Plurality of History: ASI’s monolithic narratives ignore the diversity of India’s past, reducing history to nationalist rhetoric.

Way Forward

1. Institutional Reforms: Grant ASI greater autonomy, financial independence, and professional management insulated from political interference.

2. Methodological Rigour: Adopt modern excavation methods, cross-disciplinary approaches (archaeology, anthropology, genetics, carbon dating).

3. Transparency and Publication: Mandate regular publication of excavation findings in peer-reviewed international journals.

4. Capacity Building: Improve infrastructure, ensure timely promotions, and recruit skilled archaeologists.

5. Global Engagement: Collaborate with foreign archaeological institutes to bring diverse perspectives and credibility.

6. Pluralist Framework: Encourage recognition of multiple regional civilisations and historical narratives, avoiding reductionist “civilisational monoliths.”

Conclusion

The ASI, once respected as the custodian of India’s past, is increasingly seen as compromised by political pressures, outdated methods, and lack of transparency.

To reclaim its legitimacy, the ASI must embrace reforms that ensure scientific neutrality, institutional autonomy, and methodological accountability

UPSC Relevance

GS Paper I (History & Culture)

Ancient and Medieval Indian History – archaeological evidence and excavations.

Mains Practice Question

Q. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) is increasingly criticised for politicisation, methodological inconsistencies, and lack of transparency, undermining its credibility as a scientific institution. Critically examine the challenges facing ASI and suggest structural, methodological, and institutional reforms to restore its legitimacy.