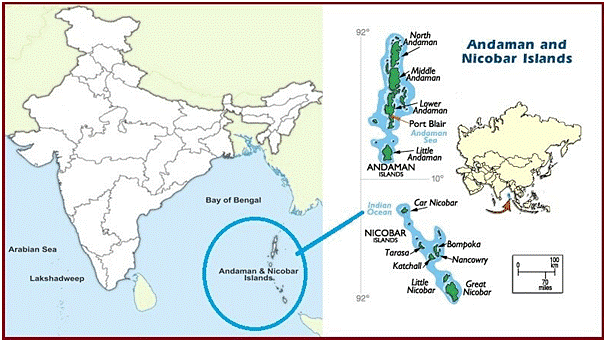

Why in News: The Government of India’s multi-crore mega project on Great Nicobar Island—including a port, airport, power plant, and township—is set to divert around 13,000 hectares of pristine forest, reviving debates over tribal rights, ecological balance, and the idea of granting legal rights to nature.

Ecological and Legal Concerns

- The Andaman and Nicobar Islands act as a global biodiversity hotspot, carbon sink, and climate regulator.

- Development decisions are often mainland-centric, disregarding the unique island ecology.

- The Forest Rights Act (2006) mandates recognition of tribal and community forest rights before diversion of forest land.

- Reports indicate the Tribal Council’s objections were ignored and forest rights falsely shown as settled, undermining due process.

- This reflects a pattern of ecological marginalisation seen earlier in projects like Tehri, Koel Karo, and Sardar Sarovar.

Judicial and Ethical Dimensions

- The Niyamgiri Hills case (2013) set a precedent by upholding Gram Sabha’s authority to decide on projects affecting tribal lands and culture.

- The Great Nicobar project raises a similar question — whether local institutions were empowered to exercise their constitutional and statutory roles.

- Ethically, it questions the anthropocentric bias in development that values human interests over ecological integrity.

- The crisis reflects a failure of environmental governance—laws exist, but implementation remains extractive and state-driven.

Rights of Nature: Concept and Relevance

- ‘Earth Jurisprudence’ or ‘Rights of Nature’ grants legal personhood to natural entities — adopted in Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, and New Zealand.

- Proposed by Christopher Stone (1972), it argues nature should be treated as a rights-bearing subject, not just a human resource.

- In India, the Uttarakhand High Court (2017) recognised the Ganga and Yamuna as legal persons (later stayed by SC), introducing the idea of guardianship for nature.

- Such a model could allow forests, rivers, and ecosystems to have legal standing in courts through appointed guardians representing ecological interests.

Way Forward

- Integrate the bio-cultural rights approach from Colombia’s Atrato River case (2016)—linking indigenous self-governance with ecological protection.

- Reform environmental decision-making to include mandatory consent of local communities under the Forest Rights Act.

- Institutionalise guardianship councils at ecological hotspots for independent monitoring and legal representation.

- Shift environmental law from damage-compensation to rights-recognition, embedding an ecocentric worldview in policy.

Conclusion:

The Great Nicobar controversy exposes the limits of India’s human-centred development model. Recognising nature as a legal entity and empowering tribal communities as its guardians can transform environmental governance from token compliance to true ecological justice.

UPSC Relevance:

GS Paper 3: Conservation, Environmental Pollution and Degradation, Environmental Impact Assessment.

GS Paper 2: Role of Tribes in Governance, Rights of Vulnerable Sections, Implementation of Forest Rights Act

Mains Practice Question:

Q. The proposed mega-project in Great Nicobar has revived the debate on granting “legal personhood” to nature. Critically examine how recognising the Rights of Nature can strengthen India’s environmental governance framework while ensuring the protection of indigenous communities. (250 words)